There is first the unremitting grimness of the Sanctuary, but when Memphis is reached, an unwelcome jokiness arises and the middle sags with too many picaresque digressions. The Left Hand of God is energetically written, but it struggles as it tries to be all things to all readers.

But would they risk an all-out war just to get him back? The Redeemers, though, for reasons of their own, haven't taken the loss of Cale lightly. There might be a chance at life here, perhaps even love. Chance allows them to enter the inner circle of Memphis's government, giving Cale his first look at the beautiful Arbell Swan-Neck, daughter of Memphis' leader. They go on the run with Cale's friends Kleist and Vague Henri, striking out across the dangerous Scablands to the decadent city of Memphis. One of the girls dies, but Cale kills the Lord of Discipline and escapes with the other. One day, though, Cale accidentally enters the room of the Sanctuary's Lord of Discipline and finds him dissecting alive two pretty teenage girls. It's run by the Redeemers, religious fanatics who regularly perform Inquisition-style tortures, and who, in fact, have "the right to kill instantly any boy who does something unexpected". Half-monastery, half-military training ground, the Sanctuary is a place of unbelievable deprivation and cruelty.

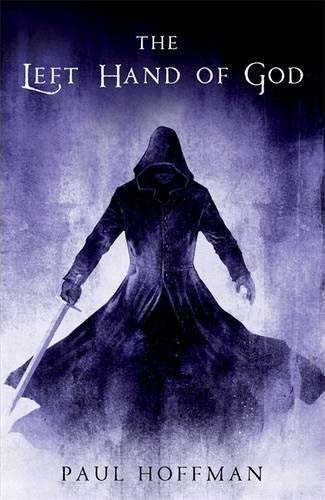

The Left Hand of God's 14-year-old hero, Cale, was brought to a labyrinthine compound called the Sanctuary as little more than a toddler, and he's known no other life. The problem, as ever, is that if you try to write a story for everyone, you run the risk of pleasing no one. It feels calculated – indeed, it feels as if it's been put through focus groups – to appeal as broadly as possible, particularly to the teenage crossover readership. Arriving on an extraordinary tide of hype – YouTube trailers, an iPhone app – it has a very readable, highly buffed sheen, but also an uneasy blending of tones whereby too many demographics are being pitched to at once. I t's hard to think of anything I've read recently that feels less like a book and more like a product than Paul Hoffman's The Left Hand of God.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)